Currents Projects

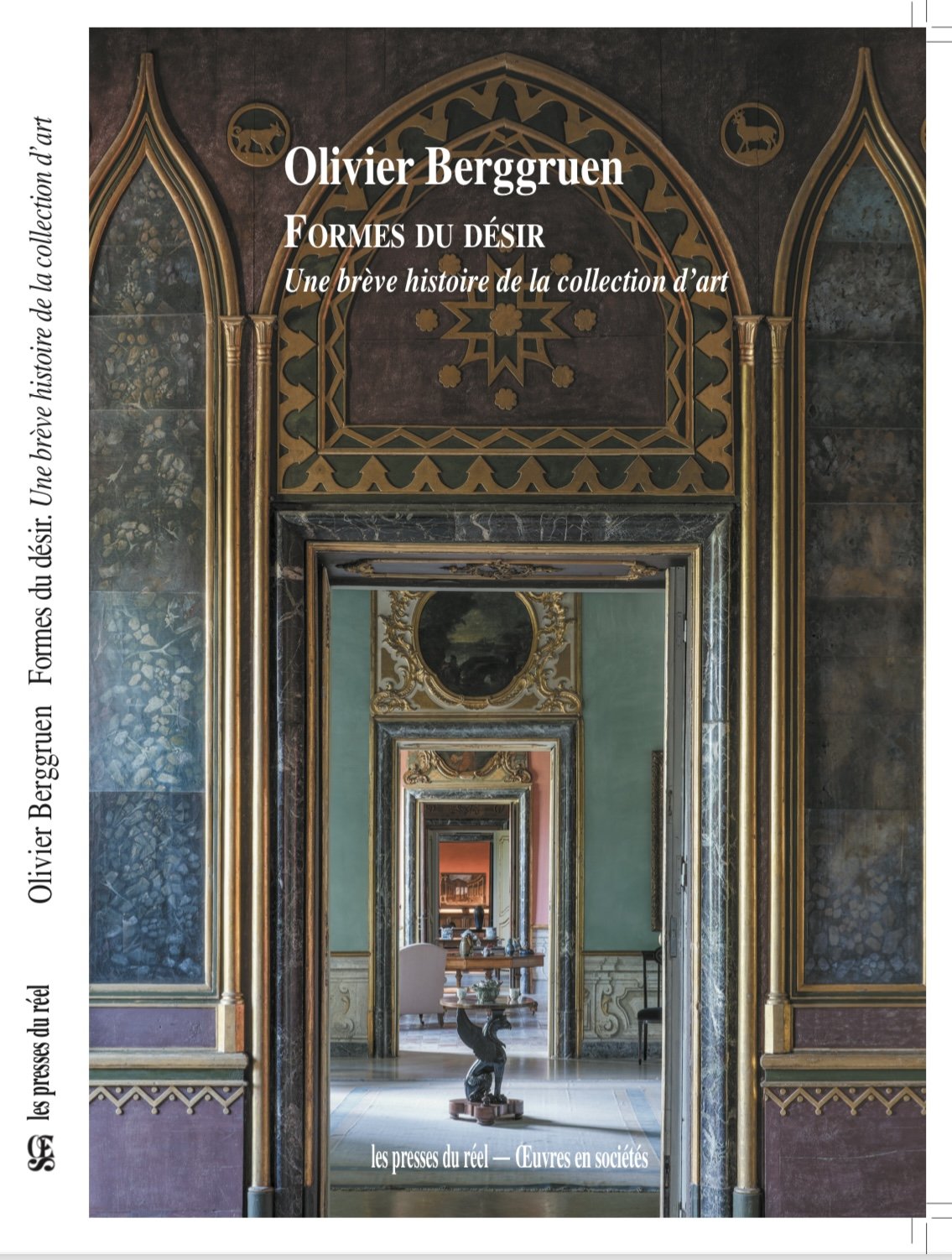

Formes du désir – Une brève histoire de la collection d'art

This history of art collecting traces a multiplicity of aesthetic attitudes through the prism of certain key figures in the history of taste. Over the course of the chapters, we discover how art collecting reflects—or responds to—an individual's character.

Past Projects

Kelsey Lu

New York, 2024

Art historian and curator Olivier Berggruen reflects on his trip to Berlin to see a performance by the multihyphenate Kelsey Lu. Following his experience of that performance, The Lucid, Berggruen caught up with Lu in New York, where they spoke about the visual elements of their work, dreaming, and the necessity of new challenges.

The Lucid: Transfigured Night

It was getting late, but I thought I had just enough time to make my way to a musical performance in East Berlin, somewhere past Alexanderplatz along the Spree River. As I passed under a cerulean sky of silvery clouds, Google Maps proved inaccurate; eventually, on a side door in an industrial area, I found a small sign announcing the venue, a new performance space called Reethaus. I walked through the front entrance of a nondescript building, exited the building through a facing door on the other side, and then followed a narrow wooden path toward what looked like a ziggurat-shaped mound. On the far side I could see the Spree. It was chilly, with the sun emitting its last rays of light. No one was there; I had miscalculated my arrival time.

When I checked in, I was asked to leave my phone in a locker and to don my shoes for felt slippers. Once I reached a terrace overlooking the river, a waiter who looked like a secular monk offered me some delicious hibiscus/cacao juice, which was refreshing. People started gathering. After a long day of travel, I found myself in a haze, as I saw a crowd of ghostly silhouettes flickering in space and bits of skin or jewelry or nylon clothing shining in random choreography. My friend Annette came up. I had seen her a few days earlier at a music recital in a baroque palazzo in Venice; although I knew she lived in Berlin, she seemed out of place here—she is a classical violinist, and I could not imagine her in a temple of experimental music. An intrepid venue for music, she said. But isn’t that what Berlin is about?, I thought to myself. Was this place trying to be too edgy? I wondered.

We waited for some time; I talked to Klaus and a few other curators and artists I knew vaguely. Then at dusk Lu appeared, silently walking in our midst, as if sleepwalking, in a diaphanous white dress and white platform boots, with cropped hair dyed blonde, their eyes lifted hypnotically toward the sky. Slowly I started paying attention, opening myself to what was unfolding before me.

Olivier Berggruen Prize

In 2021, I created the Olivier Berggruen Prize at the Menuhin Festival in Gstaad, Switzerland.

The prize is awarded each summer to a rising star in the world of piano. Past recipients include Pallavi Mahidhara, Alexandra Dovgan and Kate Liu. The prize consists of a cash award and a special trophy designed as a limited edition by the renowned artist Maï-Thu Perret.

The Fluid Gaze: Wittgenstein, Western Dominance, and Cultural Porosity

August 5, 2021 by Olivier Berggruen

In recent memory, a number of voices have emerged, questioning the dominance of a primarily Western view of art history. We see this in textbooks, cultural institutions, and museums. Some critics see it as exclusionary; it perpetuates a hegemonic discourse at the expense of historically marginalized voices, especially those of women and the LGBTQI+ and BIPOC communities. There is an assumption that the construction of cultural identity has relied on a Eurocentric way of framing visual and literary culture. In the visual arts, some critics have identified an omniscient ‘White gaze’. This gaze, a way of looking that affirms a Western, European perspective at the expense of others, has increasingly been challenged by a more plural and diverse resistance that exists outside monolithic power structures.

A closer look at how gender, race, or class have affected the construction of cultural identity in the West reveals deeply entrenched power structures within cultural institutions where these points of view have been sidelined. Our cultural biases stem from a belief that our perception of the world is tethered to notions of identity that are inscribed within a particular community. It can lead to common terms such as ‘the male gaze’ and ‘the Black gaze.’ But how could our cognitive faculties be categorized within such distinct groupings? A particular gaze may certainly be shaped by your background, how you relate to an aesthetic object within a specific cultural context. But aren’t there other things that influence the act of seeing? Can we also argue in favor of an aesthetic disposition of sorts, one that cuts across cultures?

Guest editor of the July-August 2020 issue of the Brooklyn Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2020/7/criticspage

Pencil on Paper by Phong H. Bui

Picasso between Cubism and Classicism: 1915–1925

Pablo Picasso, Arlequin et femme au collier, 1917. Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm, Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Paris, Legs Baronne Eva Gourgaud, 1965, AM 3760 P

I recently curated a large-scale retrospective of Picasso's "Classical" period. Entitled Picasso between Cubism and Classicism: 1915-1925, it took place at the Scuderie del Quirinale and Palazzo Barberini, Rome from 22 September 2017 to 21 January 2018. The exhibition marked the 100th anniversary of Picasso's trip to Rome and Naples, where he joined Diaghilev's and started a fruitful collaboration with the Ballets Russes' main protagonists, Satie, Stravinsky, de Falla, Cocteau and Massine, just to name a few.

In collaboration with Anunciata von Liechtenstein, I selected nearly two hundred works, including Portrait of Olga in an Armchair (1917), Harlequin (1917), Guitar, Bottle, Fruit Dish and Glass on the Table (1919), Two Women Running on the Beach (1922), The Pan Pipes (1923), Saltimbanque Seated with Arms Crossed (1923) and Harlequin with a Mirror (1923).

The curtain of Parade by Picasso (1917) under the frescoed ceiling by Pietro da Cortona. Installation view, Palazzo Barberini, September 2017. Photo by Alberto Novelli

At Palazzo Barberini, the grand salon frescoed by Pietro da Cortona displayed – for the first time in Rome – the stage curtain painted for Parade, an immense piece 17 metres long and 11 metres high. The architecture by Bernini framed an exciting dialogue between Picasso's work and the Baroque frescoed ceiling.

The work for the ballet Parade, with music by Satie, was the very reason Picasso came to Italy. As his friend and critic Apollinaire would say, the ballet would be destined to cause no small upset in the minds of the audience and even in the work of "Picasso the genius". Along with Parade, there were also sketches for the scenery and backdrops for the ballet Pulcinella, another theatrical production greatly influenced by the experience of the Italian tour. In Rome, Picasso saw the artwork of Raphael at the Vatican; in Naples he experienced the Farnese Hercules and the Antinous in the Archaeological Museum, in addition to the artistic and emotional impact of the mysterious charm of the frescoes of Pompeii.

The exhibition illustrated Picasso's experiments with various styles and genres, from the work with decorative surfaces in collages he carried out during the World War I to the stylized realism of the "Diaghilev years"; from still lifes to portraits.

The project was developed in collaboration with Anunciata von Liechtenstein and placed under the supervision of a scientific committee composed of Laurent Le Bon, Brigitte Léal, Carmen Gimenez, Gary Tinterow, Valentina Moncada and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso. Exhibition installation conceived in collaboration with Selldorf Architects, New York.

The exhibition was a collaboration between Scuderie del Quirinale and the Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica, conceived by Mario De Simoni and Flaminia Gennari Santori, Director of the Museum.

The exhibition's catalogue was published by Skira, and includes texts by the curators as well as by Cécile Godefroy, Sarah Woodcock and Silvia Loreti.